Cement-like soil and an unexpected lack of energy

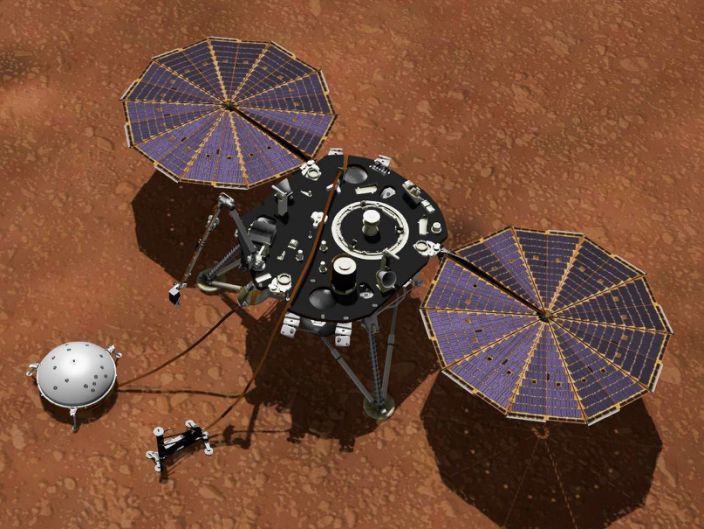

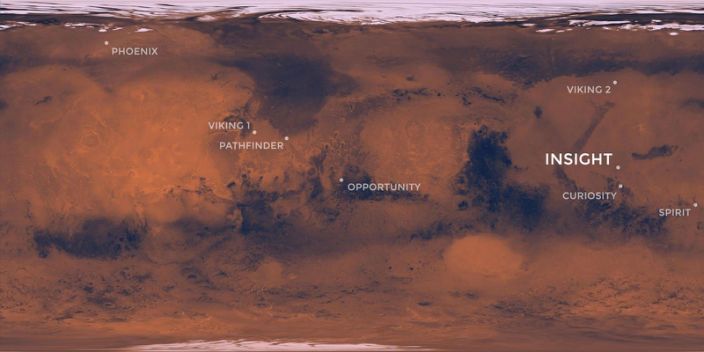

NASA has sent its InSight lander to Mars on an ambitious mission: to study the deep inner structure of the planet. An important piece of that effort – the “mole” – has failed despite attempts to save her for two years.

The Mole is a revolutionary heat probe designed to drill 16 feet into Mars’ soil and measure the temperature of the planet. His measurements would have revealed clues about how the planet has formed and changed over the past 4.6 billion years – a date that would help scientists track down Mars water, and possibly life.

But the mole made little progress in the unexpectedly thick soil. Now the InSight team must legalize solar power for landing. NASA announced Thursday that the mole will not be able to dig its burrow.

“It’s a somewhat personal tragedy,” Sue Smericar, the lead scientist on the InSight team who spent 10 years working on the birthmark, told Insider. “Everyone tried their best to make it work. So I couldn’t ask for anything more than that.”

No other Mars mission in the expected future for NASA can take the internal temperature measurements for which the mole was designed.

“It was our best attempt to get that data,” Smericar added. “From my personal point of view, it’s very disappointing, and scientifically it’s also a very big loss. So it feels like a huge disappointment.”

An unexpected energy crisis

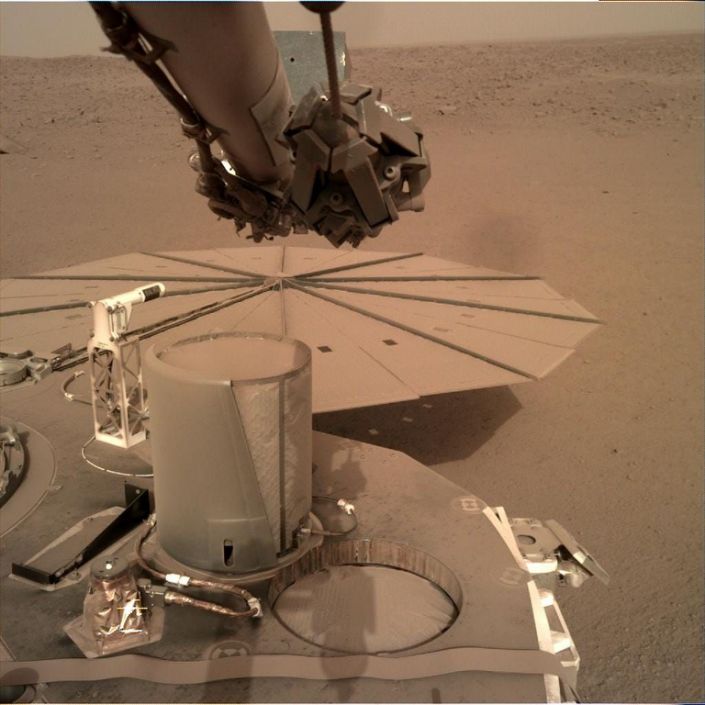

The InSight team spent two years maneuvering the landing craft’s robotic arm to see if it could help the mole dig further. The probe, a 16-inch mound driver, was designed to take advantage of the loose dirt encountered by other Mars missions. Soil will flow around the mole’s external structure and provide friction to keep roads deeper.

But in February 2019, the mole found itself resting in place on a hard soil foundation called “duracrust.” The next two years were spent troubleshooting, sending new software to InSight to teach its robotic arm new maneuvers to aid the mole, and eagerly awaiting images that might show progress.

“It was just a huge effort across the board, and it’s an effort we never expected,” Smericar said. “We thought we were going to drill the hole.”

The InSight team first directed the robotic arm to squeeze the mole, but this caused it to pop out of the hole. Once they brought the probe back to Earth, a year later, they ordered the arm to pile dirt on top of it, hoping that would provide enough friction for the probe to dig deeper.

But the mole did not make any progress with 500 hammer strikes last Saturday. Its upper part was only 2 or 3 cm below the surface.

By then, InSight’s problems were getting worse. Unlike other locations where NASA has sent rovers and landers, the open plain where Insight sits did not have strong winds. Smrecar calls such storms “clean-up events” because they blow off the red dust scattered across the planet than any robots in the region. Without it, InSight’s solar panels have accumulated a large layer of dust.

Meanwhile, the seasons were changing and InSight’s house on a flat plain near Mars’ equator was getting colder. In the event of a cold, InSight will require more energy just to maintain its function, even while the solar panels are absorbing less sunlight than they should.

“The energy is decreasing, so we are approaching a period of time where, for two or three months probably, we will likely have to move away from running hardware operations for a period of time, and then move into a stay mode getting warmer on Mars.”

With these new time restrictions, the attempt to knock on Saturday was the mole’s last chance to dig.

Over the next two years, InSight will continue to listen Earthquakes on Mars He collected data on the rumbling of the planet using its seismometer. This could provide some insights into the planet’s interior. Indeed, Mars earthquakes revealed this Mars’ crust is much drier and crumbling than scientists thought - More like the moon than the earth.

The planet’s internal temperature reveals its history

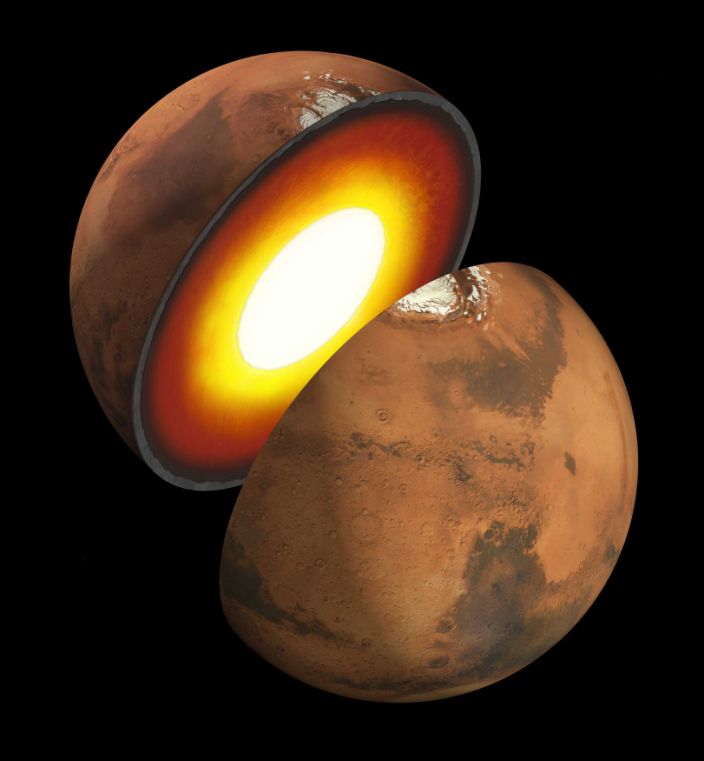

If the mole had reached 16 feet below it, it would have measured temperatures all the way down the hole. This would allow scientists to calculate how much heat is leaving Mars – a measure called “heat flux”.

“It’s number one, the thermal flux, but it has implications for all aspects of the understanding of Mars,” Smirkar said.

The heat leaving a planet is, in part, the warmth left over from its formation, but it also comes from decaying radioactive elements. The heat flux measurement will tell scientists how much radioactive material is inside Mars’ crust – the planet’s outer layer – versus the mantle below it.

This will reveal not only how materials were distributed when the planet formed (and whether it was made of the same things as the Earth), but also how the internal structure of the planet changed over time.

“This is due to an understanding of the early evolution of Mars, that period of time when there was a lot of liquid water on the surface,” Smericar said.

Increasing the concentration of radioactive materials in the mantle will make this layer more active. More radioactive material in the crust could keep the planet’s upper layers warm.

The heat flow could also indicate how deep you would have to dig in Mars to reach liquid water today. underground water On the planet it can still host microbial life. It is possible that future humans traveling to Mars would need to collect water there.

Now there is no possibility to measure the planet’s heat flux for the foreseeable future.

“I was hoping to have the data and be able to understand what that means for Mars,” Smericar said.

Read the original article at //www.everydayhealth.com/drugs/ Interested in the business